When I get a kid on my caseload who has been forced, from too early, to trace and write — for whom it is HARD to trace and write, who quickly learns to HATE tracing and writing and learns that they are BAD AT tracing and writing —

It snowballs from there. Sometimes compounded by other things. Maybe there are underlying diagnoses. Maybe the social aspect of school is also horrible for them. Maybe every day is coming to school for 50 things they’re bad at and hate doing and miserable throughout and they don’t have any friends and it feels like all their adults are adversaries.

I get a kid on my caseload like that, and they’ve been referred for “poor handwriting”, and the absolute worst thing I can possibly do for their life is sit them down with worksheets and make them write.

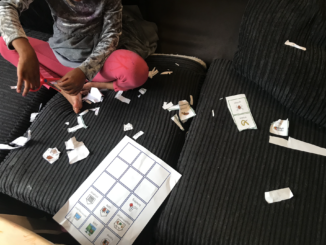

It might look to an outsider like I’m “doing nothing” for awhile, as we work on gross motor and sensorimotor activities (assuming the child finds that fun and relatable and rapport-building). And then, by the time we sit down and do manage fine motor activities, it still might look like I’m “doing nothing”.

But what I’m actually doing might look like this.

At no point did the child pick up a pencil or a marker (I’m the one who drew the racetrack). They did pick up a Q-tip covered in paint. We painted the cars different colors and pretended to be a “body shop”, we painted on the paper and raced the cars through it, and then they spontaneously also painted some shapes and lines and pre-writing shapes with the Q-tip, and it was more voluntary use of a writing utensil in 30 minutes than I’ve seen them have in the whole school year. Key word here: VOLUNTARY.

This child is the one who has to live their life, not me. Occupational therapy is supposed to be, at its very root, about “occupation”: not occupation in the sense of your job, but occupation in the sense of what “occupies” your time, the things that make up your life, whether that’s your job or your school or your play or your self-care activities. This child is the one who has to live their life, and adults have made it such that they cannot possibly relate to writing and drawing as occupation, as something they would ever voluntarily want or hope to do.

But we took a teeny, tiny step forward with Q-tips and paint and racecars, and maybe someday they will get to the point where they can write something well if they want to write it, and this is how we get there.

***

All of the above, I posted a year ago. I was writing about a child who is still on my caseload today.

I have still, in a year and a half, never made this child do a worksheet with me. All we have ever done is “play games” — exploring fine motor and gross motor activities, supporting the development of this child’s sensory processing systems, self-regulation, upper arm strength, core strength.

The closest we’ve ever come to “structured work” is playing a typing game on my iPad that is offered as one of the stations in my room every week, and which lately this child really enjoys and frequently chooses to do. Even then, we don’t play it “right”…some days the child hops straight to the hardest mode and plays levels that are way above their skill level, pecking out letters slowly…and sometimes they choose ones that are well within their wheelhouse and work on learning how to actually touch type.

And, in class, this child is writing. This child is writing *well*. Slowly, yes. Harder time than other kids, yes. With immense amounts of support from not just me but other providers, yes. But…they’re doing it. They’re getting there. They no longer feel on the defense. They no longer hate it.

They wrote a letter to their teacher to tell their teacher why they love their class this year. I read it and cried.

A year ago, I said, “Maybe they will get to the point where they can write something well, if they want to write it.”

And this year, they did. They did want to write it. And they did.