Okay, after my last post, you might be asking, how do we give kids power and autonomy?

Honestly, a different way to ask this same question might be, how do we protect their right to their own power and autonomy?

Because in the absence of adult interference, kids will find the ways that they want to be autonomous and they’ll make it known to us what it is they want!

I have one child (who I’m the mom of) who was utterly uninterested in ever dressing himself and one child who started learned to dress and undress at about a year and a half old! The freedom to choose what she was wearing, or to wear nothing at all, was interesting and important to her, whereas my son just didn’t care. I could give him choices all day long about “do you want this shirt or that shirt,” “do you want to try to buckle your shoe or do you want me to do it for you” and it would not contribute to his feelings of autonomy and power – it would annoy him, because getting dressed and undressed is an interruption to whatever other thing his mind has going on at that moment.

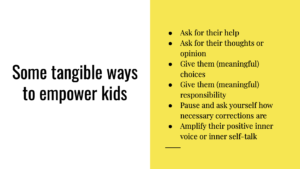

So a lot of times I’ll see the suggestion that offering kids choices is equivalent to giving them power and autonomy, and in some ways that’s the root of some truth. But giving them meaningless choices, or using choices to try to trick them into doing the thing you want? Kids see right through that. They get decision fatigue just like adults do, they don’t want meaningless choices. They want to choose the things that matter to them.

This is why I’ve seen classrooms where they let the kids choose flexible seating to do their work – they can sit in an office chair, on a yoga ball, in a beanbag, on a wobble stool, on the floor, whatever they want – and some kids will still just choose to sit in a regular chair at a regular desk. For those kids, this choice isn’t that important, or they’re fine with what’s considered the status quo. But for the kids for whom the choice is important, this can be a massive difference in their ability to focus.

Another huge part of this goes back to what I said earlier about letting children be in charge of their own brain and their own emotions. Even if that means the child is feeling upset with you, or angry…even if they roll their eyes, or slump their shoulders, or trudge away from you after you’ve said something. I see a lot of adults feel that they need to add even more correction in that moment and correct the child’s emotional expression. In my opinion, jumping further on them with correction right then is just kicking them when they’re down.

They’re five, or eight, or ten. They’ve been living on this entire planet for a handful of years, and someone is telling them something they don’t like, and they’re feeling an emotion about that and communicating that emotion with their behavior.

Forcing them to resentfully suppress those feelings to appear outwardly pleasant for your own sake is a really big way to signal, “I have all the power here and you don’t even get to own your own emotions.”

I know some adults who feel really strongly about this because they think the children won’t learn to be respectful or to hide their feelings in an adult, business context or other concerns like that. There’s also some really legitimate concerns about kids’ safety with unsafe adults – adults who won’t give them the benefit of the doubt, who aren’t willing to see the kids’ perspective, who have the authority to hurt them because of how they’re acting or reacting. That might be law enforcement, it might be the child’s parents, it might be teachers or other authority figures in their life. But I have never ascribed to the idea that we need to preemptively hurt kids in order to stop them from being hurt by somebody else. I think this is an area that there’s a whole additional conversation that could be had, but it’s at least worth being mindful about when correcting a child for “being” or “emoting” the wrong way.

Another really important way to practically empower kids: to reduce their reliance on your praise in favor of amplifying their own positive self-talk and their own inner voice.

I’m not saying don’t praise your kids or don’t tell them when you’re proud of them, or that you appreciate them! But I do think there are small ways to shift language to help them listen to their own inner voice that will be there when you’re not there someday. You can do both: if they show you something they’re proud of you can ask them, “How do you feel about that?” Or observe their behavior by saying what you see: “I see you’re showing me your blocks and you’re smiling! You look so proud of yourself!”

It’s important to bring in the concept that it’s not only the adults that they need to be listening to on this—because someday you want their self-worth to be coming from themself; not relying on the approval of other people. It can be very empowering for children for us to be attentive and focused and delighted by what they’re telling and showing us, but bringing our words back to reinforcing how they feel about themself and not only how you praise them.

To end on another positive note and suggestion: a really quick and profound way to give children a surge of power and self-esteem, too, is to ask them for their thoughts and truly listen, or to ask them for their help with something and then truly let them do it. Of course, if you already have an antagonistic relationship with a child, this is a tough one to be the bridge into letting them have more power, because what you see as “letting them help”, they might see as “you making them do something”.

But if you already have a connected relationship with a child and you ask them to run an errand for you, or ask them their thoughts on a question that there’s not a right or wrong answer to recite, or you give them a responsibility in the classroom or in the hallway or over the class like handing out papers or holding the door or whatever it is…they take ownership of that. They feel proud that you entrusted them with something. They learn to manage a teeny little corner of the world. And that’s exactly what power is, at its best.