“Strengths-based” evaluation, goals, or treatment is something of a brand-new buzzword in the field of occupational therapy. And sometimes OT professionals feel threatened by this phrase, or feel like it leads to euphemistic evaluations where we just have to gloss over things that are legitimately difficult for the child.

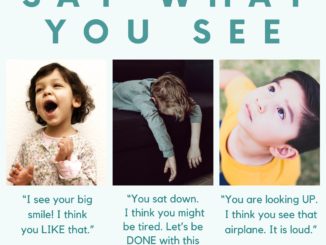

I think there’s some merit to writing evaluations and goals and developing treatment plans for children that start with their strengths, though. I think that strengths-based assessment doesn’t have to be euphemistic or falsely positive. Rather, I’d say it involves changing the lens through which I see children, describing what I actually saw instead of falling back on jargon or empty phrases, and describing what was needed for the child to be successful.

Here’s an example of what might go in an occupational therapy write-up from a traditional, deficits-based observation of a child:

“Tyler presents as extremely low-functioning. His play is non-functional. During free time, he typically throws objects around or stims. His play is rigid; he does the same thing over and over. If confined to one place, such as a chair at the table, he will have negative behaviors like spitting. When therapist tried to engage him in joint activities, such as blowing bubbles, he seemed to like it but made no attempts to communicate or ask for more. He does not visually engage with others.”

(In my own history, I have written write-ups like that. This is not me just dragging what other providers do. This is me reassessing what I, myself, have historically done and written. I sometimes believed, or was even overtly told, that I needed to write things with a negative bias so that they would sound “bad enough” to justify OT treatment.)

Here’s an example of how I might write about the same child today.

“Tyler is currently completely engrossed in his independent sensory play. He loves to seek auditory, tactile, and visual input. He tends to follow the same paths of play with minor variations to explore how these small variable changes affect the outcome – for example, he will throw many objects to the floor to listen to the slight differences in sound that come from the different materials, different shapes, and different floor surfaces. He is unselfconscious about meeting these needs any time or place that feels right to him, and with methods such as playing with saliva that sometimes present health and safety concerns in the school environment. Tyler doesn’t yet seem to understand that the adults around him want to play with him or share new experiences with him, although his adults keep trying. He will sometimes attend to novel play experiences – when therapist blew bubbles for him, he looked up, smiled, and flapped his hands among the bubbles, but did not visually appear to follow where the bubbles were coming from or that the bubbles were related to therapist trying to play with him.”

With kids, we’re (usually) not rehabilitating something that’s been lost. We’re starting from the beginning and trying to grow into whatever they grow into. And whoever it is that they grow into is going to be based on what they love and what their strengths are, not how big their deficits are. The work I do with Tyler is, especially at first, going to be largely based in intense, focused sensory exploration because for him, that’s his whole world and joy and occupational meaning right now. There’s no point in me writing his evaluation talking about him like that’s a bad thing and that everything about him is bad and wrong.

I describe what I saw with as little bias as I can, because maybe I won’t understand exactly what every reason for everything he does was in a 1-hour timespan, but I might be able to look back on it later and figure it out with more context. I can’t do that if I’ve already mentally assigned negative biased reasons for everything that a child does. I’m not glossing over the fact that some things are difficult but neither am I falsely making those things catastrophic, nor the only meaningful thing about the child. I assume that everything he does has a reason for it, and I write according to that assumption.