This post is a transcript for this one, which has the video.

I want to start by asking you to think about learning. What comes to your mind when you hear the word learning?

Maybe you think of classrooms…whiteboards…maybe you think of your own high school or college experiences, or of lectures, teachers or professors.

Now I want to ask you to think about play. What comes to your mind when you think of play?

Of children playing?

I think most people think of something very “stock photo”. Children laughing and spinning on a merry-go-round. Or children stacking blocks.

When we are talking about children – especially children from birth through 7 years old, but even on up through the rest of childhood and even on into the rest of the lifespan – most scientists who study brains and learning actually agree that learning and play are very closely linked. Not two separate things at all! The most powerful way for children to learn is actually to play.

Too often, adults will get in the way of children playing because they may believe that those other things are more important. This could be parents, teachers, caregivers, grandparents, babysitters and in my experience they almost always have good motives, they’re very well-meaning about it. They see play as something “extra” for kids to do when there’s nothing better to do, but they want their child to have a rich and meaningful life, so they may even spend a lot of effort, time, or money to try to make sure their child does have something “better” to do than just play. Or they might have something that feels very important to them, so they try to spend the child’s time teaching that important thing to the child. These adults may not realize just how important play is to child development!

This starts happening in the baby years and continues all the way up. Babies need to practice reaching out for things and grasping them, rolling themselves over, sitting themselves up, and getting between one position to another even when it’s frustrating. These types of play are called locomotor play–playing with movement for movement’s sake. Rolling over just because it’s really cool to face this way now. Learning to scoot around or crawl because it’s amazing to move your hands and knees at the same time. Just like all types of play, locomotor play can involve struggle and even frustration. But it’s really hard and awkward to watch another person struggle with something, even when that struggle is important! So a lot of parents will swoop in to save their child from that frustration.

In toddler years, there can be the exact same difficulty with locomotor play on a larger scale. Toddlers may get frustrated when they can’t climb up a ladder on the playground or can’t jump high enough to reach something high, so their parents lift them up it or hold them up. The parents might even try to give the child verbal instructions about how to do it, when children really learn best by trying it out with their own body and figuring out how it feels–by playing!–instead of by listening to a lecture. And gaining these body skills through struggle instead of taking shortcuts is extremely important because they’re actually the foundation of writing skills, which I’m going to talk about more in a little bit.

There are lots of other forms of play, too, than just locomotor play.

Toddlers do a lot of exploratory play, which is play that involves throwing things, banging things, dropping things, and so on. Adults might put a stop to that because toddlers don’t know the difference between what objects are a good idea for that kind of exploration and what objects are a bad idea…so if the toddler tries to throw Mom’s phone, or drop food off their high chair at mealtime, the adult might see it as “bad behavior” instead of what it is, a developmentally normal play phase that the child is supposed to go through. (It’s much more successful to give the child loads and loads of access to things that they are perfectly welcome to throw and bang and drop!)

Toddlers also do a lot of object play where they are closely examining and exploring objects and those objects’ interactions with other objects. They might find some small random thing that isn’t even a toy and become fascinated with it, or they might try to take things apart to see what’s inside them or put things together in unique and creative ways. This is all very basic to us, but do you know why? It’s because we did that kind of play when we were toddlers! They’re laying the foundations for being able to come up with creative problem solving skills later in life, and understanding all kinds of the foundations of things later in life.

As children get into the preschool years there are even more types of play that they start exploring. Children go through an explosion of types of play in the 3-5 age range!

Preschoolers do a lot of rough-and-tumble play which is like wrestling, pretending to hit or fight but not actually intending to hit or fight, etc. In many contexts, especially at school or daycare, it might not be allowed for children to engage in this kind of play. There are good reasons for that, as long as all the adults keep in mind that it’s perfectly developmentally normal for the children to *want* to do it and to keep *trying* to do it, because the children are following their body’s normal development. Punishing them for doing something that their brain is telling them is natural and necessary is really harsh and hurtful. We definitely don’t want to teach them that they will be punished for listening to their body’s needs. We just want to teach them that they can trust their adults to help keep everybody safe, even if that means stopping something fun.

Preschoolers also do tons of role play and socio-dramatic play which is two forms of acting out things that they see in real life. This is how they make sense of the world around them–by pretending to act like moms and dads, like teachers, like doctors, like people who can drive cars, like people who work at shops, like people who give haircuts. Their brains are asking and sorting out all kinds of questions like, what is the essential nature of this activity? What do grown-ups gain from engaging in this activity? What’s important about it? How are other people involved? Why does society work the way it does? What part do I play in all of this?

Closely related, preschoolers do lots of imaginative play and fantasy play with make-believe elements and saying things that aren’t really real. Children at this age are still exploring the difference between what is real and what is fantasy, so they often believe what they’re talking about. They’re sorting out the values of honesty vs happiness and delight, like, if you ask them a question and the honest answer will make you sad, they might think that it’s kinder to tell you the answer that will make you happy–because most preschoolers would rather hear things that make them happy, not things that are true!

Toddlers, preschoolers, and elementary aged kids will all do creative play, but it often looks very different across the age-span. Toddlers and preschoolers are usually more interested in process art, which is using creative materials for the sake of exploring the creative materials and what they can do. Older children are often more interested in product art, which is focused on creating a finished product that looks like something they had in mind when they originally began. Both of these are really important and having the appropriate one for the right age is really important. I have more to say about creative play when I talk about the foundations of writing in a few minutes, too.

A couple of types of play are more evident mainly in older kids, elementary age and even older. Those are communicative play and social play. These both involve playing with words, making jokes, lots of verbal things. These also involve communicating to complete a shared goal, like figuring out the rules of a game together, or verbally planning about what it is that you want to build out of building materials. These are also often the way that adults play! I make jokes by saying something with a double meaning that only my husband or friend might understand, or by saying things that are sarcastic. I like playing board games and party games that involve us all talking about the game materials–a common type is ones where you lay down a card and then the judge has to vote on which card fits the prompt the best. These types of things involve communicative play and social play.

So you can see that there are so many forms of play that happen across the span of childhood and they take many different forms. And they’re incredibly important, and each form of them is the child’s brain learning something foundational that it needs to know to build up into the higher skills like learning in an academic context, being able to draw conclusions from data, being able to solve problems, being able to work together, being able to understand yourself and what needs you’re having. All of these things spring up from children having literally thousands of hours of access to playing.

I talked about how locomotor play is the earliest form of play that even babies will explore. And I talked about how difficult it can be for adults not to try to step in and make it easier for them! There are some really important reasons to try to let children explore their body’s movement at their own pace. Of course you don’t just ignore them when they’re in distress, but there are lots of degrees of helping out and encouraging without just doing things for them.

That’s because all humans’ bodies develop strength from the core first, then working outward. The core muscles, the muscles that control your trunk, to lean and wiggle and rotate, are the first things that develop. Next are the muscles of the biggest joints that are the closest inward…the shoulders and the hips. Then it continues outward from there. Next are the elbows and knees. Then the wrists and ankles. Then the fingers and toes. It’s going from inward to outward.

The thing is, children need LOTS of strength in their core to do things like…be able to sit up without needing to lean on something. That’s true for 6-month-olds but it’s also true for 6-year-olds! Many kids do not get the chance to develop enough core strength. They tend to be very floppy and lean or drape on furniture, other people, the back of their seat, their elbow on the table, because their core is not strong enough to hold them up for an extended period of time. Core strength is important for baby milestones like rolling over, sitting up, crawling, walking. It’s also important for older children. You can’t do monkey bars or a cartwheel without core strength. You can’t sit upright and sit still without core strength. You can’t walk steadily in the hallway without leaning on things or fatiguing without core strength. It’s really the heart of almost everything humans do in a day and tons of things that children have to do at school.

And it develops naturally through play if children are given the chance to play for enough hours before these things start becoming expectations! If they have enough time to put themselves into weird positions and crawl into tight spaces and climb things and flip themselves upside down and then right side up again and roll around and jump around and run around, their cores get stronger and stronger!

I mentioned how the joints develop from inward to outward, too. The shoulders need to be strong and stable before the elbows, before the wrists, before the fingers. Think about how babies learn to reach for and pick up objects. First they’ll learn how to basically fling their entire arm in the direction of what it is that they want, and maybe touch it or slap it. Then they’ll learn to slowly refine that movement until they can reach for something and grab it with their whole hand opening and closing. And over time they learn to pinch at something small with their fingers, or to pick it apart or pinch pieces of it or twist it or interact with it. They’re still learning that into toddler years!

So then three-year-olds and four-year-olds need to be doing tons of work to strengthen and stabilize the bigger, closer-in joints before they are working on things that take the smaller, further-out joints. And that “work” is their play. They need to carry things, push things, pull things, pour things, scoop things, pinch and twist and dig and hammer and smash and break and rip and pick at and build and squeeze a zillion things before all those muscles have developed the kind of coordination it takes to do incredibly precise tasks like writing letters or buttoning small buttons or cutting with scissors.

I called this talk “Protecting the Power of Play” because this is something that absolutely, completely needs to be protected–because it’s currently under attack. Again, it’s not an attack on purpose. It’s not because adults are just mean and want to hurt children. It’s actually the exact opposite. It’s with pure intentions, because adults want to do what’s best for children. And so the adults think about what kinds of demands and expectations there will be for children when they get to kindergarten or first grade, and they think that they’ll help make the world a little easier for the child by trying to start teaching them things ahead of time.

The problem is that their bodies just physically are not ready for that yet. Children cannot learn what they are not ready for–and on the flip side, once they’re ready for it, they will become super fascinated by it and seek it out!

I noticed this happen in my own life with my son. He’s my first child, and I wasn’t finished with school yet when he was born, so I didn’t know everything about child devel opment that I learned and studied over time yet. He’s a really tall and big kid. When he was somewhere between a year and a half, two years old, I was super frustrated that he wouldn’t climb into his own car seat. It sounds a little silly for me to even say it, but to me he looked visibly big enough, he could climb up on the couch and climb up on simple stuff at playgrounds and stuff, and to me it seemed like he was just purposely not climbing up into his carseat when I told him to do it. I was so annoyed by having to lift him up into his carseat every time. He was heavy and sometimes I was carrying groceries or stuff but here I was always having to lift him in.

Well, covid hit when he was about two and a half, and we were living in different places and we ended up pretty much really sheltering from the world for a very long time. He really rode in a car almost none at all for about a year and a half straight. We went a few places, but the way our life ended up working out, I could probably count on one hand the number of times that he rode in a car during that time period.

When the restrictions started to relax and we started going places again, I remember I opened the car door one day and he just climbed right up into his seat. I had long since forgotten that I even cared about this, it didn’t hit me until he just…did it. I hadn’t been making him practice, I hadn’t been insisting that he even try, I had just totally given up and forgotten about it over that full year and a half and always lifted him into his seat. And as soon as his body was ready to actually do that skill, he just…did it. Immediately.

I’ve seen the same thing happen with my own children, and with the children that I work with as an OT, literally dozens if not hundreds of times. Their adults might believe that they’re ready to do something independently, or that they should be able to. The adults might be sure that it’s just bad behavior or a bad attitude or that they’re not motivated and that’s why they’re not doing it. But as soon as the child is able, then they want to do it, because kids want to be independent. Of course there are times when something else is more important to them…when they want to feel cared for, in the same way that I sometimes ask my husband to get up and get me a drink from the fridge even though I’m perfectly capable of doing it for myself, because I want to feel loved and cared for. But trying to stand over a child and insist that they do something that they’re just not ready for, like insisting that a three-year-old or a four-year-old write letters because it’ll make kindergarten easier for them eventually, is like trying to prop a two-month-old baby up on their feet so that they’ll learn how to stand and walk! It just doesn’t work. Their body isn’t ready for it yet and no amount of “practicing” will make their body do a better job at it when they are ready for it–and it might even hurt them in the meantime.

Toddlers and preschoolers might be very interested in markmaking tools, like pencils, crayons, and markers. Or they might have no interest at all. That’s because there isn’t one set age where children are interested in drawing and coloring, though almost all of them will go through a phase at some age where they’re interested in it, unless their adults have made it into a demanded and disliked activity. Sometime between about 18 months old and about 4 years old, most children will go through a phase where they realize that objects like crayons, markers, etc can make marks on things. If they’re like my daughter, they might be way more into making marks on their own skin than on paper!

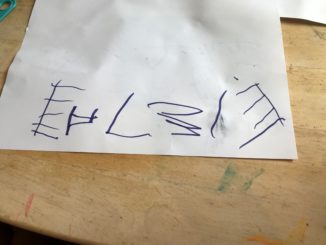

The first marks they make are usually either scribbles, or long, random lines.

The next thing that develops is usually more focused scribbling in vertical, horizontal, and circular patterns.

Scribbles are a very important stage of development! Letting kids scribble is not just letting them waste paper or stopping them from doing what they need to do later on–just like letting them crawl isn’t stopping them from learning to walk; it’s the first step and it’s an important step in and of itself. Think about how you, an adult, would color in a coloring sheet. How do you fill a big swath of the page with the same color?…you scribble! You probably scribble in, like I just said, vertical, horizontal, or circular patterns, depending on what the size of the field you’re trying to fill is. That’s exactly what this step is for! It teaches children how to start and stop, going in one direction and then stopping and coming back in the other direction, which is so so important.

The next thing they learn is to make horizontal and vertical individual lines, that are not attached to a scribble, and usually how to make circles, again, that are not attached to a circular scribble. These come from refining the skill of stopping and starting at the right time, because you have to start drawing the line, then stop when it’s just one line and not keep coming back to make a scribble.

Then they learn how to do three hugely important skills: drawing on the diagonal, crossing midline, and abruptly changing direction. Drawing on the diagonal is so tricky because it requires the brain to figure out how to draw horizontally and vertically at the same time. If you ask a child who is too young to try to copy a diagonal line, they’ll usually make either a vertical or a horizontal line because their brain just can’t make both movements at once.

Crossing midline is also really tricky because it engages both sides of your brain. If you ask a child who is too young to try to copy a cross, they’ll usually start at the middle and draw outward both ways because their brain isn’t seeing it as one shape…the left half of their brain is controlling one half of the shape, and the right half is controlling the other half of the shape. That skill hasn’t integrated yet.

Changing direction is tricky because it means your brain has to have already made the plan. A circle is kind of an ongoing curve, it doesn’t require quick decisions or quick motor plans. But a square, for example, requires you to know where your hand is going and follow the plan your brain has made. If you ask a child who’s too young to try and copy a square, they’ll usually make a very rounded one or maybe flat-out make a circle.

If children can’t cross midline or can’t draw diagonals or can’t change direction, they are NOT CAPABLE of drawing letters. All of these skills MUST be in place before children can draw letters.

Think about how many letters have a diagonal in them: Y, X, V, W, Z, N, K, A, Q, and that’s just uppercase!

Think about how many letters cross midline…A, M, N, t, H, X…

And all of those also have abrupt changes in direction. Any letter with a corner or a point, like B, N, M, P, L, E, W, X, V, F, Z, A…

I get referred children all the time in kindergarten and even sometimes in first grade who just physically can’t form the letters yet because they have not had enough time for their body to practice the underlying skills yet. They may not be able to write their name correctly if it has those letters in it and they’re missing one or more of those skills. And trying to make them practice when they’re 3 and 4 doesn’t actually make them any more able to do those skills–it just makes them feel bad because they can’t do it and it might even make them dislike it, especially if their adult thinks they’re not doing it because they’re unmotivated or disobedient rather than because they’re literally not physically able to do it.

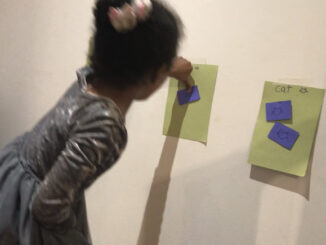

On the flip side, there are always a few 3-5 year olds who are interested in writing and may even be good at it already. That’s because kids can have very different skill sets depending on what they’re interested in. There’s nothing wrong with letting children pretend to write by scribbling out long loopy lines, or even write if they already know some letters or words. It should just be following the child’s interest instead of being forced by adults. They might use writing or pretend-writing in their other types of play that I already listed– like role play and socio-dramatic play. They might pretend to be a teacher, pretend to make a grocery list, or pretend to write down an order at a restaurant. These are all great and shouldn’t be discouraged! They also shouldn’t be corrected if they’re doing it technically incorrect, like writing a letter backwards or writing letters that don’t make sense or spell a word. The play and exploration is exactly what they’re supposed to be doing to work on those skills.

If they’re not interested in writing and drawing, they might still be interested in other aspects of play that support the skills they will need to write and draw. There are lots of skills that require your body to be able to do two different things with your two hands at the same time. Some of these skills are relevant to art and work in school…some of them are just relevant to life, like cutting paper while holding the paper, writing on paper while holding the paper, zipping a jacket while holding the jacket, climbing a ladder on a playground, driving a car someday! Playing freely and playing lots of games that involve both hands strengthens this skill that supports cutting and writing and stapling and glueing and painting and all kinds of things later on. Throwing and catching, climbing, swinging, things that require alternating sides of your body like playing hopscotch, riding a trike, riding a bike, dancing, playing musical instruments; things that require coordinating both sides of your body at the same time like jumping jacks, catching a ball– all of these things are important for strengthening the “both sides of your body” skill that’s called bilateral coordination.

They might also be interested in using glue, tape, playdoh or clay, a hole punch, paint, stickers, glitter, pom poms, pipe cleaners, popsicle sticks, recyclables, or a million other things they can explore and use to work on the foundational skills!

If they’re not interested in writing or drawing with pencils or markers or crayons, they might be interested in using a q-tip to paint. That’s the same skill building! You have to pinch it with your fingertips and manipulate it to make marks on the paper.

If they’re not interested in coloring on a coloring sheet, what about on an easel, on a whiteboard or smartboard, or using chalk on the wall outside? Writing on a vertical surface instead of a horizontal surface strengthens your shoulders and elbows–the important big joints!–because you have to hold your arm up while you’re working instead of being able to rest it on the table. Or what about coloring or painting on 3D surfaces, like painting with washable paint or drawing with chalk on plastic cars? That does the same thing with upper arm strengthening.

All those skills I mentioned earlier like crossing midline, drawing on the diagonal, and starting and stopping abruptly are all skills that happen in the small muscles for fine motor activities like writing, but they’re also skills that happen in the big muscles like moving your whole arm or your whole body. So drawing with chalk on the ground or on butcher paper on the ground or coloring something huge on the ground are amazing ways to work on those skills in the big body sense.

And you can even tape paper to the underside of a table or a chair and have the kids color or draw above themselves, which combines both skills in one–moving the whole body and strengthening the arms and core!

There’s another skill that’s developing at the same time alongside all of these motor, movement skills. It happens in parallel to all of these other things, and that is sensory processing. “Sensory” is almost a little bit of a buzzword these days but it originally comes from my field, occupational therapy. When we talk about sensory processing, we’re talking about the different senses that are in your body. You probably learned about these when you were a kid: your sense of touch, hearing, sight, smell, taste. There are more senses than that too–actually quite a few more–but in occupational therapy, and in child development, we typically also talk about our vestibular sense (our inner ear sense of balance and motion), our proprioceptive sense (our deep body sense of pressure and our sense of our body in space), and our interoceptive sense (our internal body sense of interpreting our body signals to understand our physical sensations, like hunger, and emotions, like anxiety).

I could talk for a whole hour about just sensory processing, but I’ll try to give a super brief overview on another important thing here. People–not just kids, but all people–tend to have some forms of sensory input that they have a low tolerance for, and some forms of sensory input that they have a high tolerance for. Some people have a low tolerance across the board for almost everything–sight, sound, smell, taste, and so on. Some people have a high tolerance across the board and they might be the thrill-seeking kind of people in life! But most people tend to have a mix of preferences.

Another way to think of these tolerances is thinking of them as like a cup. If the cup overflows, the person does not feel good. It feels like overwhelm and with kids it might be a meltdown! But if the cup is too empty, that also doesn’t feel good. Kids are often seeking to fill their cups at least part of the way every day.

If kids are doing something a lot, they probably have a “big cup” for that particular sense. A kid who is touching everything around the room probably has a “big cup” for the sense of touch. A kid who flinches when others touch him or even get too close to touching him probably has a “little cup” for his sense of touch–and it feels like that touch might pour too much into his cup, overflowing into overwhelm.

Most children, especially under the age of 5, have a big cup for their proprioceptive sense. That’s the one I said is your sense of deep pressure, your feeling of where your body is in space. Children tend to be a little bit clumsy. Part of that is their motor coordination at work…their muscles and their movement and all of that. But part of that is also just their sense of where they are in space compared to other things. Children often like deep pressure from squeezes or hugs, that’s deep pressure, that’s proprioceptive sense. Children will often squeeze themselves into tight spaces. Children often like jumping around on a trampoline or a couch or gym mats, these things are all their proprioceptive sense. It helps their body make sense of its surroundings. It helps their body get a sense of groundedness.

The proprioceptive sense, the one I’ve just been talking about, is also a very calming sense in that regard. That’s why getting a big hug from someone you love can be very settling and calming to your body. There’s an emotional component to it obviously but there’s also a very physical component to it.

When I work with kids who are struggling with their sensory processing, they might be becoming overwhelmed by things around them or they might be seeking to fill up their cup so extremely much that they’re bothering other people with the ways in which they do it, when I work with those kids, the first things I usually do are all proprioceptive things. Pushing and pulling, jumping, wiggling, squishing with a beanbag or a pillow, if it’s appropriate giving them a hug– these things all give a calming sense of groundedness to most children.

Proprioceptive and vestibular input – that’s inner ear sense of balance and motion – are hugely important for self-regulation and for brain development. Children age 3-5 will often not be able to sit still for more than 3-5 minutes and that’s because of how their brain is developing these senses. They are not supposed to sit still for very long. They are supposed to move, wiggle, fidget, climb, roll, crawl, balance, jump, spin, and run! These things are influencing their core strength and joint stability and sensory processing. And each of these things support school skills later in life. And these are the years for them to do them!

That’s why we need to protect opportunities for our kids to be able to develop all of these skills through play. They will be the supports that make it possible for them to learn to write, read, use scissors to cut out shapes…and be a good friend, take turns, walk in line in the hallway, and interact with all kinds of people. These are the supports that make it possible to live the rest of their lives, and they only have a few years where this is what their brain can and should completely focus on. You guys, working with the youngest ages, have the opportunity to make that happen.