On this site, you will always see me saying “Autistic person” (or its variants, Autistic adult, Autistic child, etc) instead of “person with autism”. But you might have heard (just like I did in school) that it ought to be the opposite! What is the story there?

Person-first language is a movement that rose up in professional circles (i.e., teaching, mental health, healthcare, etc) with good intentions — to refer to people as “person with ____” instead of “_____ person”. There were many reasons for this.

For one, there is a tendency, especially in medical circles, to start referring to people as only their diagnosis. In a hospital rehab setting that might sound like, “I have a new hip on my caseload”, where the word “hip” actually means “a person with a hip fracture”. You can see how this quickly becomes demeaning. “I’m not available right now, I’m just about to go see the new spine” — you’re not even referring to them as a person at all. It was medical shorthand, but it was a little too callous.

For another, there is a tendency to use disorders as descriptors or even as adjectives themselves when they are not. “Oh did you hear they have a Down syndrome kid?” Down syndrome is not an adjective. It is a noun, a name of a syndrome. Or, even worse, “They have a Downs kid” or a “Downie” or other words that have historically been used as pejoratives.

In response to all of this language use, which was hurtful to the people hearing it and may have been callous or insensitive on the part of the person speaking it, there arose a movement to call people instead by, literally, person first language. It’s right there in the name: they’re a person first. A person with a hip fracture; a person with Down syndrome.

However, disability is not just one thing and people with disabilities/disabled people (there’s an example of person-first and identity-first) are not one unified front who all think and want the exact same thing. Obviously. So what is more appropriate for one community or one subset may be different than what another wants — and even within a community, what an individual wants may be different. For example, the community of adults with Down syndrome have largely expressed that they do, in fact, prefer to be called adults with Down syndrome – and so I honor that, the way that they have asked to be called.

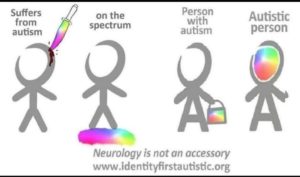

As a whole, many (if not most) of the Autistic community prefer identity-first language. There are good reasons for this too. You don’t say “a person with gayness” or “a person with Blackness” — you say a gay person or a Black person, and nobody gets concerned that we’re forgetting that those are people. Another way to say it is, Autistic is, in fact, an adjective, and using it as one is not *inherently* pejorative (although it is sometimes used as an insult, and shouldn’t be). So, for people who prefer identity-first language, they dislike the implication that autism itself is so inherently negative that it has to be treated like some special kind of adjective that can’t just be an adjective.

Another reason why many Autistic people prefer “Autistic person” to “person with autism” is that they don’t feel that autism is a removable trait from themselves. It’s not something “with” them the way that an object would be with them, physically nearby them. It’s something inherent in them; it is a part of them. Removing it or distancing it with language feels awkward and unnecessary. This carries over into “has autism” vs “is autistic” as well. A lot of Autistic people prefer to say that it is who they are, versus being something they have (as if it were catching, or a disease, or ever going to go away).

Again, I emphasize that even within a community, there may be individuals who feel differently about any given topic. There are absolutely some people with autism who prefer to be called people with autism. You should always defer to what a person specifically asks for.

I have found that the vast majority of Autistic people prefer “Autistic people”, so it is usually my default when I am writing not to a specific person, but to or about a large and general group. I have also found that many (non-autistic) parents (of autistic children), for one reason or another, prefer “person with autism” when speaking about their child. Depending on the context in which I am approaching that scenario, I may go with their preference or I may gently educate them if there is already an established and appropriate relationship for that.