[Though I don’t currently have the bandwidth to accept any new consultation requests by email, I am still working through the backlog of consults that I did with people a couple of months ago when I was able to accept those. Here’s another of those questions.]

***

A parent wanted to know about ways to support their child who is unaware of the personal space of others. The way that this manifests for the child is that they are making big, sudden movements in class—possibly related to self-soothing when they are anxious about something in class—and getting in other people’s space in ways that could be unsafe (if they accidentally hit, kicked, or ran into somebody else).

Though this is a very niche question, I also think that it can be generalised more largely outward. Maybe everybody’s kid isn’t shadowboxing or kicking their legs out when anxious in school, but there are lots of children who have a lower awareness of others’ personal space and/or movement needs that are higher than what usually “fits in” in a traditional classroom setting.

To me, there are 3 components of addressing this:

1. The need being expressed and the exact way they’re currently expressing it could be taken as: The child sometimes needs space to move in a big way.

2. The current environment where the need is being expressed could be taken as: The child needs a way to move in class that is safe for everybody.

3. The thing that’s NOT working right now needs a way to communicate about what’s not working right now: The teacher needs a way to gently and non-threateningly remind the child when they’re being unsafe or help them to be safe.

This breakdown could also apply in lots of areas of life, this 3-part breakdown.

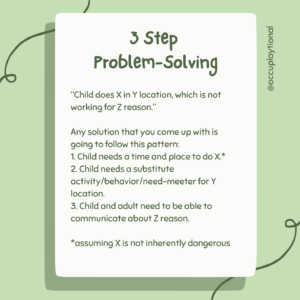

“Child does X in Y location, which is not working for Z reason.”

Any solution that you come up with is going to follow this pattern:

1. Child needs a time and place to do X.*

2. Child needs a substitute activity/behavior/need-meeter for Y location.

3. Child and adult need to be able to communicate about Z reason.

*assuming, of course, that X is not harmful in and of itself, but only due to location/other factors. If X is inherently harmful then obviously we don’t find a time and place for them to do it, but we just accept that step 2, finding a substitute, may be more complex and also more important, and step 3, being able to communicate and remind them, is also probably more complex and more important.

My problem-solving strategy when applied to this specific situation, sounded like this:

I wonder whether building some time in to this child’s day — more time, if there already is some — where they know they can specifically go do large movements, would help at all? It might possibly get some of the “energy out” in advance.

As an example from my own life, I am a very excitable person and often get overwhelmed with excitement at small, delightful things. I am pretty good, in adulthood, at going and standing in the bathroom stall, or closing my office door for a moment, so that I can literally take 10 big jumps up and down, or flap my arms with extreme delight, for a few moments. Then I can go back into the work that I’m doing. It feels like an intense energy release that helps me keep my other stimming movements throughout the day at a manageable level — like fidgeting with a fidget at my desk, instead of needing to overtly stim.

I do this mainly due to the fact that in a professional context, I need to at least somewhat keep my large-body movements to myself. I also do this because I love it, it feels like a delightful little secret with myself about how happy and excited I sometimes feel and getting to take a moment to revel in that joy.

It might feel very different for the child in the original question if their movements are rooted in anxiety, so I cannot say that this is a 1:1 comparison. Still, I wonder whether making a plan (with the child as a co-partner in planning!) like, “In between x class and y class, I will go to the bathroom and do 5 air punches” or “after lunch and before we come back to class, I can go outside and do 5 big air kicks” would help?

In addition to having a time to do “big movements”, it might help to have a designated “small movement” or a designated menu of 3-5 small movements at their desk that — again — they are a co-partner in developing and practicing at a time when they’re *not* already anxious, not already in class and trying to focus, etc.

For example, using a particular fidget, chewing on a piece of chewelry to get proprioceptive input through their jaw, adjusting their position in his chair so that they’re sitting on a foot or kneeling in order to get more proprioceptive input through their legs, squeezing or wringing their hands to give them some strong sensory input, eating a strong-tasting candy, mint, lemon drop etc to give some alerting feeling to their mouth…etc.

(These are just some examples, not an exhaustive list.)

So overall, the goal would be:

1. Make time and space for the big movements,

2. Come up with some little movements to help “in the moment” but practice them “out of the moment”, and then maybe

3. Come up with a silent signal from the teachers.

I like that idea and have some ideas like that with kids I see in schools. It can be a two-way system: they could have a silent signal to tell the child, “Hey, you’re disturbing other people/getting in their space/hurting somebody — remember to be careful!” and the child could also have a signal to tell them, “Hey, this feeling in my body is SO STRONG that I need a break right away, I’m going to the bathroom” or whatever. That way, it’s two-way communication and check-ins — not like they’re just handing it down to the child.

One thing that has worked for some of my kids in the past is having a small note or symbol on their desk. It could be laminated and taped to the desk for durability, and then the teacher can casually walk by and tap the note or symbol to help remind the child. Alternately, it could be a loose card (still laminated if possible), and the child or the teacher can flip the card over in order to catch the other’s attention. (i.e., if it’s green on one side/red on the other. Or something like that)

This hopefully helps you understand both the theoretical side of understanding this 3-step process for helping problem-solve along with a child, as well as a very concrete set of suggestions for one example of a particular problem being solved according to this 3-step process.

[Image description:

A pale green background with dark green curlicues on it, with a white page over the top of it that reads, “3 Step Problem-Solving.”

Then there is text with the paragraph from in this caption that describes most succinctly the theory laid out here:

“Child does X in Y location, which is not working for Z reason.”

Any solution that you come up with is going to follow this pattern:

1. Child needs a time and place to do X.*

2. Child needs a substitute activity/behavior/need-meeter for Y location.

3. Child and adult need to be able to communicate about Z reason.

*assuming X is not inherently dangerous

The image also has my handle on it, @occuplaytional. End description.]