I spoke to a parent recently whose child was getting in trouble at school for being too “touchy” with other children—wanting to hug, touch, wrestle, tickle, etc more than was school-appropriate or allowed.

I know these types of kids, too, and my heart really goes out to them! Rough-and-tumble play is a powerful and important type of play in childhood, and just because there are good reasons that it can’t be allowed in a school setting doesn’t mean that the instinctual need for this type of play goes away in a child.

The parent was worried that they were making the child’s “behavior” worse by encouraging all kinds of this behavior at home, where both parents and all children were enthusiastic and would roughhouse and tickle and play and giggle with one another. I very quickly told them that I would say the exact opposite—the child DEFINITELY needs this need to be met at home! Taking away *all* available avenues for it would not at all help the need in the child’s body go away.

This is really a very expected and understandable age-appropriate behavior. As with anything, that doesn’t mean that it has to be allowed to continue unchecked. But it helps to keep in mind that it’s not shocking or something the parents are doing wrong.

There are always a few kids who are “too touchy for school”. The problem is that young kids are supposed to be touchy-feely in all things — it’s how they learn, grow, meet sensory needs, etc — and that touchiness extends to touching other kids too. Wrestling, roughhousing, etc. It’s completely and totally a societal thing to say, here is this place where we need to have a bunch of young kids and also they’re not allowed to touch each other.

Again — that doesn’t mean that I’m saying it doesn’t make sense or there aren’t reasons for it. But anytime that we go against what is totally normal and age-expected, even if it’s for good reasons, there are going to be a few cases where they have a hard time meeting those expectations because…they’re doing something normal and age-expected.

So what to do about it? I have three answers here. One is to keep giving the child an outlet for all that energy at home, or in playdates with other children.

One is to keep talking about consent and stopping when someone says to stop, while also realising that it might take years and years for that to set in, just like with anything about self-regulation skills does with children as they grow and develop. It is a long-term developmental growth trajectory for children to realize, “hey, other people are different than me”; and then, “hey, them being different than me means they might want other things than me”; and then, “hey, them wanting other things than me might mean that when I’m happy, they might *not* be happy at the same time”, and so on. This is a long game. It involves a lot of playing and talking and trial and error and correcting and trying again. It involves a LOT of the parent or adult patiently correcting and reminding without getting annoyed, angry, or shaming that the child should already know this by now.

The final component is to tell the child what they CAN do. The reason why this takes some skill and work on the part of the adults is because a child could be meeting LOTS of different needs by touching, hugging, wrestling with, and tickling others at school. Any or all of them might be applicable, and any or all of them might need a suitable replacement. For example, looking at just tickling:

1. Tickling is funny and makes other people laugh, I like to make other people laugh. A replacement could be: learning to tell jokes, learning to verbally make people laugh, potty humor, making silly faces, etc.

2. Tickling is a good way to get to wiggle my hands (movement in my hands) and touch something with my hands (tactile to my hands), I need that. A replacement could be: holding a fidget, flapping hands, running hands over cloth, fidgeting with hoodie strings or shoelaces on own clothing, etc.

3. Tickling makes me feel connected with the other person, and I love that person. A replacement could be: other age-appropriate friendship things with peers, other connection opportunities with adults.

4. I tickle the other person because I actually hope they will reciprocate and tickle me, and I want touch and pressure on my body! A replacement could be: wearing tight clothing or weighted or spandex clothing, or an undershirt beneath the regular shirt; wearing a heavy jacket or hoodie or coat inside; getting a big hug, etc.

There are more factors — these are far from the only four! But imagine if these *were* the only four, you could see how coming up with a replacement for the child isn’t as simple as just swapping it out with one thing, but might require different things at different times.

At the exact moment when a child is tickling somebody that they shouldn’t be, the adult should have an immediate thing they can cue him to *do* differently (not just to *not* do), like, “Hey, I see you’re trying to make Sarah laugh! Remember what we talked about personal space at school? You could play with your fidget while we talk about something silly if you want to, I’d love to chat with you!”

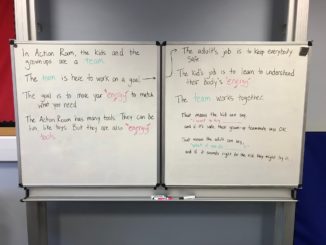

These three steps really mirror my “three-step problem solving” process that I’ve talked about here before, where the question is, “Child is doing X in Y location and it’s a problem because of Z, what do I do?” and my answer is:

1. Find a time and place where child can do X,

2. Find a substitute behavior for child to do in Y location, and

3. Child and adult need to be able to communicate about Z reason.

The communication in point 3 comes in two prongs—both the adult being able to redirect the child “in the moment”, and the conversations about consent and stopping play when someone asks you to stop that happen ongoingly too.

A unique factor in this specific problem-solving case: I often find in these kinds of discussions with parents, especially parents of boys, there’s some amount of shame in the parent for feeling worried about how their son will turn out as they get older, because this is such a fraught topic in our world today. And rightfully so, there have been lots of important society-wide discussions about consent and body safety. It can make parents feel worried if their young children don’t seem to be “getting it” as fast as the parent feels like they ought to.

I promise you that if you are feeling any of that, this is an extremely normal thing for young children to go through and have to learn how to have societal boundaries around. It doesn’t spell out anything about their future, their moral character, or any of that. An impulsive little boy (or girl! But there is a unique component to parents of boys right now, too) who loves to play, roughhouse, and make people laugh means nothing at all beyond them just being a sweet, bouncy, innocent, happy child who loves to make people laugh!

It’s not the child’s fault that our world is the world that it is. The parent does not need to project all their worries about living in the world onto their child’s shoulders. Having adults around them who can nurture the lovely and joyful parts of their personality while also gently guiding them toward understanding how to respect others’ boundaries too is super crucial, but a big part of that is understanding that what the child is currently doing is not bad, morally wrong, or a predictor of frightening slippery-slope futures. It is normal for children to touch other people. It is normal for children to be so wrapped up in their own joy that they don’t notice someone else isn’t feeling the same way. It is normal for children to need their adult’s help in these interactions. Some of that just takes time!