Modeling writing authentically and meaningfully and delightfully doesn’t always have to be, like, great works of prose or poetry. They don’t even have to make sense or be meaningful to someone who wasn’t using them for play. That’s what academic writing is for. Notes jotted down in one’s own notebook, words scribbled out as part of a game, ideas brainstormed before drafting the final draft? Those don’t have to make perfect sense. The pursuit of perfection is sometimes a little bit paralysing when it gets all tangled up with play. I don’t want to let that stop me.

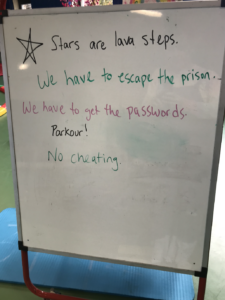

As a student was dictating to me what the rules for this week’s game of “The Floor is Lava” would entail, I grabbed a whiteboard marker and started writing down exactly what he said.

He paused and protested, “You don’t have to write those.”

“Oh—but my brain forgets a lot of things,” I said to him. “I want to know exactly what you say because it’s important.”

“It takes too long,” he countered.

I pointed at my words and said, “I already wrote everything you said and I’m ready for any more rules. I will write pretty fast.”

He thought about it for a few minutes. Then he muttered under his breath, “Well, it *is* important…” and then, at conversational volume, “Okay. The last one is the most biggest rule: No cheating.”

“No cheating,” I echoed as I wrote it. “Okay. Got it.”

“Now come onnnnnn, let’s already playyyyyy,” he told me, and I grabbed my “treasure” (a weighted sensory bottle) and turned to balance across the balance beam back to where he was.

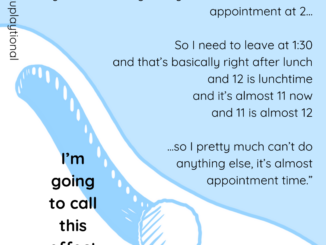

Later, we were drawing roads with chalk on a yoga mat on the floor for toy cars to drive around in. “I’m going to draw a park,” he announced, shortly followed by, “I’m going to write ‘park’ on it. So you don’t forget it in your brain.”

“Awesome. Thank you so much.”